The current focus on deficit reduction has government leaders scrambling to find places to make significant cuts. Congress and the President are currently grappling with what to do about farm subsidies – namely the nearly $5 billion direct payment program that pays farmers and landowners year after year regardless of circumstances, and the federal crop insurance program that costs taxpayers between $6–to–$8 billion a year.

President Obama, at least, has recognized that direct payments are completely unnecessary and unjustifiable in today’s booming farm economy. A look at farm incomes today shows that the President is right – direct payments should be on the deficit-reduction chopping block so that other truly valuable programs can be spared.

Last year I wrote a piece examining farm household income as it relates to the subsidies that many farms and landowners get from the government. By and large, America’s farmers and ranchers had a very good year in 2010 and are looking to have an even better one in 2011. Net farm sector income (after subtracting the costs of doing business) is projected to rise by 31 percent over 2010’s already strong levels, to $103.6 billion. This is the highest ever, and the second highest in inflation-adjusted dollars, since 1973. This year’s droughts, floods and storms have certainly left some farmers high and dry, but those who have crops or livestock products to sell are doing very well indeed.

Nevertheless, billions of taxpayer dollars are set to go out in direct payments to the very same farmers and landowners who are having a banner year. Wheat is expected to bring in 37 percent more cash this year, corn will be up nearly 39 percent, soybeans up 17.5 percent, and cotton will be up almost 29 percent. Of the five major subsidized commodities, only rice growers are doing poorly. Meanwhile, unsubsidized vegetables will only see an increase in cash flow of 8.6 percent, and fruits and nuts will only inch up 2 percent.

What justification can there be for subsidizing growers of exactly those crops that are producing the best returns?

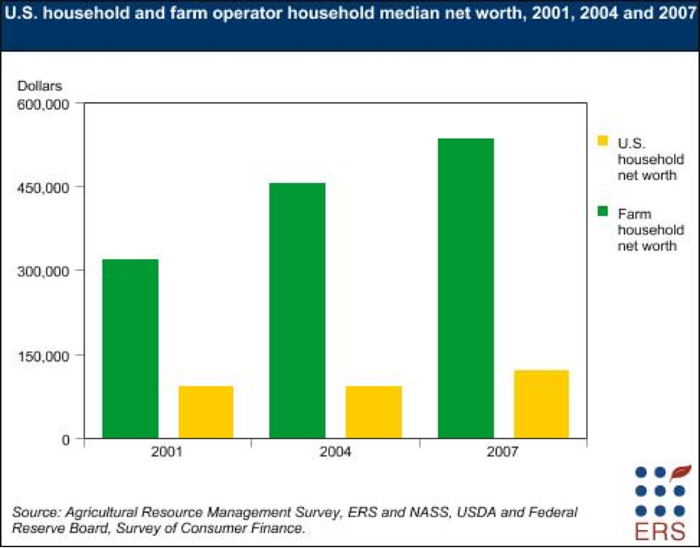

Farmers’ wealth is also expected to jump this year, thanks to strong income and the continued rise in rural land values. Farm sector net worth is forecast to rise 7.7 percent while farm sector debt decreases, matching the record-low debt-to-asset ratio set in 2007. Meanwhile, the housing sector nationally (the main measure of wealth for most families) has declined by almost $1 trillion over the last year, according to the Federal Reserve.

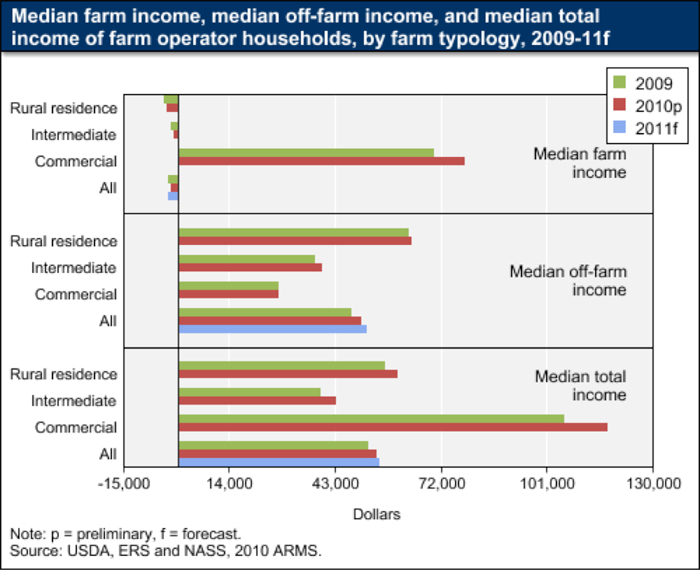

Moreover, median farm household income in 2010 was $54,370, $5,000 higher than the median income of all U.S. households and at least $14,000 more than other rural households. This year, median farm household income is expected to rise by 1.9 percent, to $55,405.

The biggest farms, those with gross sales of more than $250,000, are doing particularly well. Their median household income in 2010 was $117,854, an amount sure to rise again this year. Only smaller farms are projected to suffer a decrease in income from last year, and as the chart below shows, these farm households make nearly all of their money off the farm.

The net worth of farm households has skyrocketed because of the run-up in land values in farm country. Subsidy advocates wishing to stave off cuts have always claimed that farmers are land-rich and cash-poor, but they never told us just how land-rich farmers really are. Median wealth for farm households was more than four times the average American’s in 2007. This relatively very large wealth gives farmers better ability to weather economic ups and downs than non-farm families, better retirement security and more access to equity and capital.

Nonetheless, farmers and landowners making the most money and accumulating the most wealth continue to rake in the most of the government subsidies.

This is why farm subsidies have become such a focal point in the federal budget debates going on in Washington and around the country right now. At a time of record farm income, many people are asking, “Why are taxpayers sending billions of dollars every year to people who make more money than I do?” Even President Obama in his recommendations for deficit reduction called for cuts to farm subsidies. His report noted:

Farm income has been high and continues to increase, with net farm income forecast to be $103.6 billion in 2011, up $24.5 billion (31 percent) from the 2010 forecast – the highest inflation-adjusted value for net farm income recorded in more than 35 years. The top five earnings years for the past three decades have occurred since 2004, attesting to the profitability of farming this decade.

The President’s report then goes on to say that against this backdrop, direct payments in particular are indefensible.

… [T]axpayers continue to foot the bill for these payments to farmers who are experiencing record yields and prices; more than 50 percent of direct payments go to farmers with more than $100,000 in income. Economists have shown that direct payments have priced young Americans out of renting or owning the land needed to enter into farming. In a period of severe fiscal restraint, these payments are no longer defensible, and eliminating them would save the Government roughly $3 billion per year.

The President’s statistic about the majority of direct payments going to farmers making more than $100,000 is just the start.

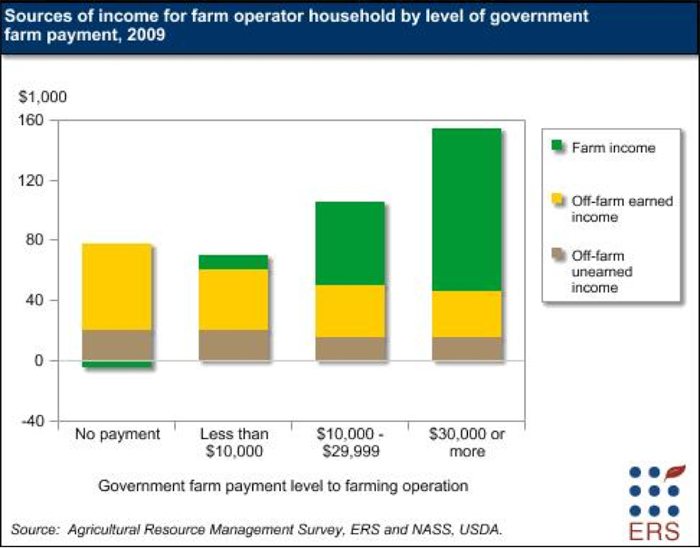

According to the US Department of Agriculture, farm households collecting $30,000 or more in government payments in 2009 had an average income of $154,019 – three times the average of all US households. Meanwhile, farm households getting less than $10,000 had an average income of $70,047 in 2009. That was still more than most US households, but far less than went to the farm households receiving the biggest government payments. Farm subsidies are very poorly targeted to need and very highly targeted to those at the top of the size and income scale. EWG’s Farm Subsidy Database consistently shows that the top 10 percent of subsidy recipients take in 74 percent of the money.

At EWG, we don’t think this is the right way to be spending scarce taxpayer dollars. We didn’t think it was right during the boom years (at least for the non-ag economy) of the 1990s, and we don’t think it’s right now when the American economy is struggling mightily and agriculture is booming.

The counter-argument from the heavily subsidized industrial agriculture lobby and their supporters in Congress is that it makes sense for the biggest producers to get the most money since they produce the most food and fiber. This point actually exposes the twisted reality of our current farm policy.

Contrary to popular belief, agricultural subsidies have never been a social policy aimed at helping struggling farm families. Since the 1930s, farm subsidies have been industrial policy with “American Gothic” as the façade. If the objective were to support individuals and families who are in special need because of their line of work, then sharp means testing would be the rule – it isn’t – and the government’s money would be targeted to those who need it most – it’s not. Instead, the nation’s farm policy has always been about producing as much food and fiber as possible, with the government there to buy up and ship out the extra and to pay farmers when surpluses depressed prices. Industrial farming techniques, chemicals and machinery have advanced dramatically, but individual farm families have been left behind in the arms race, and subsidies have done nothing to stop the trend, or even slow it.

The question for policymakers intent on cutting the federal deficit is not whether “farmers” still need government support, but rather: Does the agriculture industry still need the unique level of support it currently enjoys? Or are there better and more fiscally responsible ways to support working farm and ranch families that are truly in need of help while enhancing the diversity and long-term productivity and sustainability of the industry as a whole? The answer to this question is decidedly “yes,” and the debate over deficit reduction offers the perfect opportunity to move policy in the right direction.