Across U.S., Toxic Blooms Pollute Lakes

TUESDAY, MAY 15, 2018

TOLEDO, Ohio – In the middle of a muggy summer night, Keith Jordan got an urgent text: Toledo’s tap water wasn’t safe to drink.

“I thought it was a joke," said Jordan, who works with at-risk youth in Toledo’s inner city. He went back to sleep. When he got up a few hours later, he took a shower and had a cup of coffee, then turned on the news.

“They were saying don't drink the water, don’t take a shower – the water is messed up,” Jordan said. “You couldn’t even touch the water. It was something you could not believe was happening here in Toledo.”

That was Aug. 2, 2014. For the next three days, half a million people in and around this industrial city at the western edge of Lake Erie scrambled to find safe water.

Many drove hours across state borders to stand in long lines at stores that hadn’t sold out of bottled water. Some stores were charging $40 for a case of water that usually costs less than $5. Jordan, unaffected by his shower and coffee, helped set up distribution centers for free water, and helped deliver it to seniors and mothers with babies. The National Guard sent tanker trucks full of drinking water to the city.

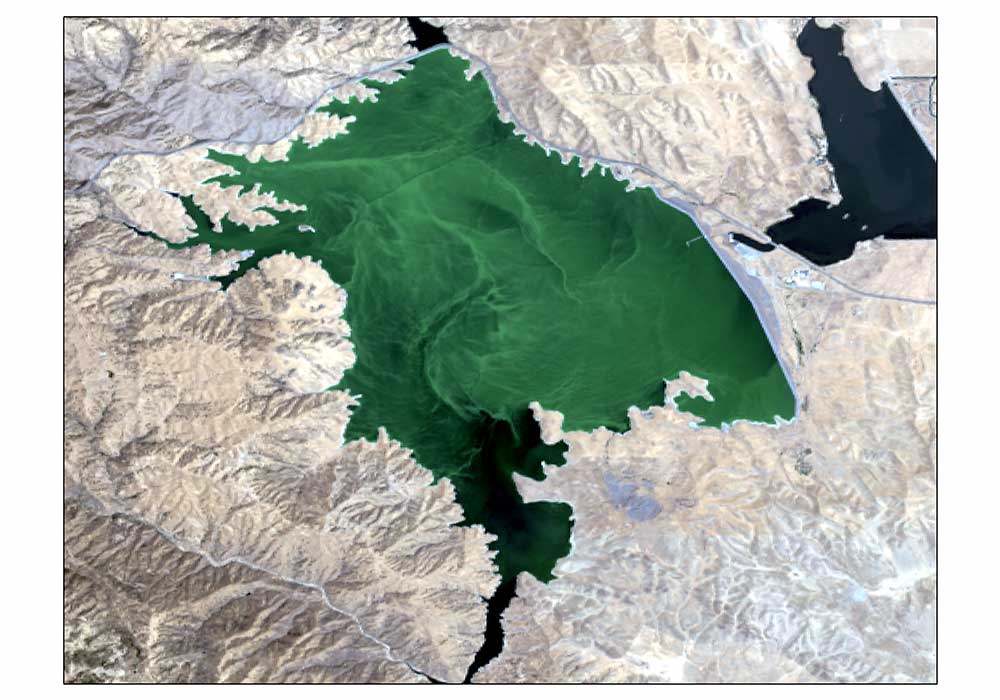

The panic was set off by a toxin called microcystin, the byproduct of an enormous bloom of blue-green algae that had invaded Lake Erie. The bloom – technically not algae, but photosynthetic single-celled organisms called cyanobacteria – blanketed vast expanses of the lake with what looked like thick, sickly green split-pea soup. It was triggered by chemical pollution from farm fertilizers and industrial sources into the lake, which supplies the region’s tap water.

Toledo was the first large U.S. city where toxic blooms made tap water unsafe for human consumption. But it may not be the last.

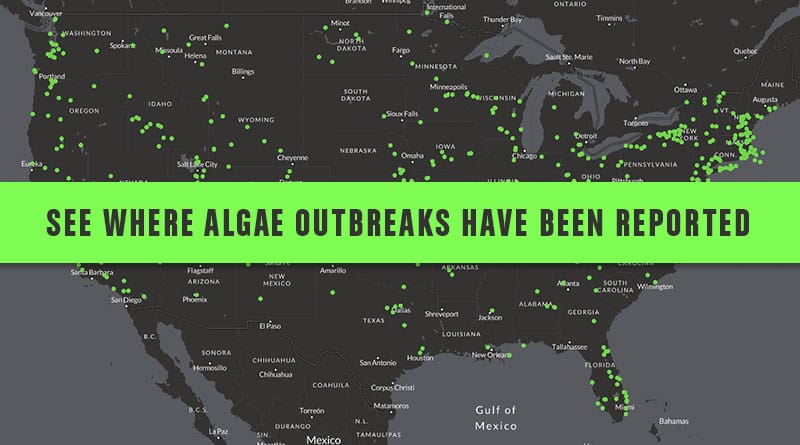

No government agency collects nationwide data on toxic blooms. But EWG’s research found news reports of almost 300 blooms in lakes, rivers and bays in 48 states and the Gulf of Mexico since 2010. Based on those reports, the problem appears to have worsened over the past few years.

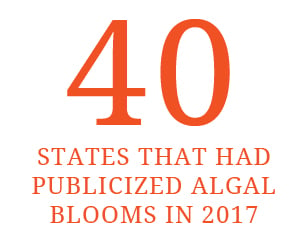

In 2010, there were just three reports of toxic blooms in the U.S. In 2015, there were 15, including the largest to date in Lake Erie, although the bacteria did not get into Toledo’s drinking water. In 2016, there were 51, including a huge bloom in Florida that prompted the state to declare an emergency in four counties on the Atlantic Coast. Last year, 169 blooms were reported. And in March, Ohio Gov. John Kasich declared the open waters of western Lake Erie “impaired for recreation” – an unprecedented designation that under the federal Clean Water Act will require the development and enforcement of plans to reduce toxic blooms.

EWG’s interactive nationwide map shows locations of reported toxic blooms in green.

Cyanotoxin blooms are a worldwide problem, according to Sandy Bihn, executive director of Lake Erie Waterkeeper.

“We’ve seen them in Australia, there was a bloom in Brazil where the microcystin actually killed people, they’re in China,” Bihn said. “In the Great Lakes, some of the bigger areas that have them are Saginaw Bay and Green Bay. We have [seen blooms in] Lake Okeechobee in Florida, the Chesapeake [Bay], the Gulf of Mexico. We’re all connected to this problem in many ways.”

Notable U.S. Algal Blooms

Algal blooms don’t always produce toxic microcystins. When they do they’re not just a gross and smelly nuisance, but can pose serious health hazards to people, pets and wildlife.

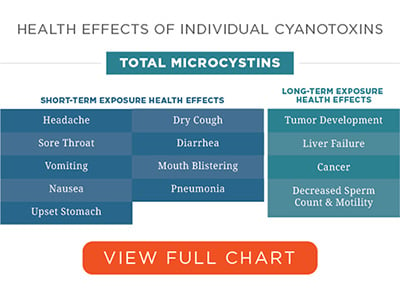

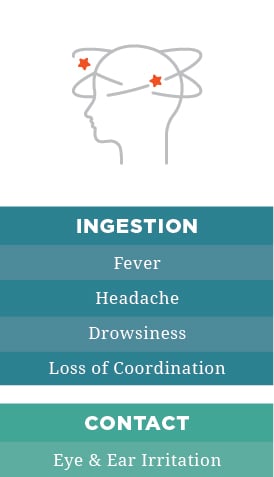

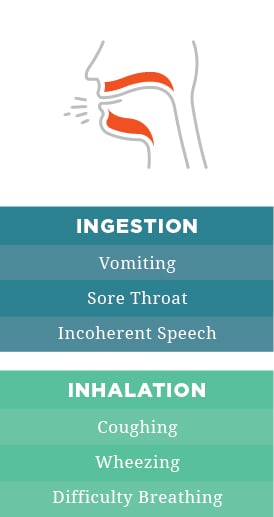

According to the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (PDF), some microcystins are more dangerous than any other water contaminant besides dioxin, the notorious poison in Agent Orange. Whether through ingestion or skin contact, short-term exposure to microcystins can cause sore throat, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and liver damage. Long-term exposure can lead to cancer, liver failure and sperm damage.

Data on illnesses linked to toxic blooms are spotty. But a study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that in 2009-2010, 61 people in Ohio, New York and Washington state got sick from exposure to toxic blooms in freshwater lakes. Two-thirds of those affected were teenagers or younger children. The CDC said this suggests children may be at greater risk of illness from cyanotoxins, due to more frequent exposure to and ingestion of the water. 1

A New York State Department of Health survey of 16 counties found that in the summer of 2015, 32 people and three dogs got sick after recreational use of lakes contaminated with cyanotoxins.2 That same summer, a Michigan man reported he was ill for months from handling fish he caught in Lake Erie, and the East Bay Regional Park District, near San Francisco, closed five lakes after three dogs died. In June 2016, 130 people reported vomiting, diarrhea, headache and rashes after swimming, skiing or fishing in Utah’s largest freshwater lake, which was almost completely covered by toxic blooms.

In addition to the health hazards, toxic blooms devastate western Lake Erie’s recreation economy, which brings in billions of dollars a year.

During a toxic bloom, visitors to the lake’s white-sand beaches are greeted by signs warning against swimming or any other contact with the water. Sandy Bihn of the Lake Erie Waterkeeper lives near a state park on the south shore. She said that during Labor Day weekend last year, when one of the largest blooms of the decade forced closure of the beaches, the park was “dead silent, just eerie and sad.”

Dave Spangler, vice president of the Lake Erie Charter Boat Association, has been taking anglers out on the lake since the 1970s.

“We’re the walleye capital of the world, with many, many people from all over the country and even out of the country who come here to fish,” he said. “But [during the record bloom] in 2015, we had people with reservations call after seeing the pictures of what the lake looked like, and they just said, ‘I don’t think we want to go.’”

“We had to shut down for six or seven weeks, right in the heyday of our season,” Spangler said. “We got hit by 20 or 25 percent losses, and so did the bait and tackle shops, and all the rest of the businesses that rely not just on fishing but other forms of recreation.”

The conditions that trigger cyanotoxin blooms vary by location. In Lake Erie, they occur when too much phosphorus and nitrogen wash into the lake’s shallow west end, usually after a heavy rain in the summer months. The blooms don’t erupt until the water gets warm, then subside once the weather cools off in the fall.

The chemicals get into the lake from a number of sources, including power plants and sewage treatment plants. But the National Center for Water Quality Research, at Heidelberg University in Tiffin, Ohio, says the “inescapable conclusion” from 40 years of study is that the main culprit is phosphorus runoff from commercial fertilizers and manure applied to farm fields.

Much of that runoff comes from the Maumee River, which flows into the lake through the heart of Toledo. The river drains an area of more than 8,300 square miles in Ohio, Indiana and Michigan, and according to Waterkeeper, more than 70 percent of that land is used for agriculture. Besides millions of acres of cropland, the western Lake Erie watershed has 140 concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, which produce an estimated 630 million gallons of animal waste a year.

“We’re all connected to this problem in many ways.”

- Sandy Bihn

Under an agreement with neighboring Michigan and the Canadian province of Ontario, Ohio has set a goal of reducing phosphorous runoff into the lake by 40 percent in the next seven years. For years, the state has tried to address the problem by encouraging farmers to take voluntary steps to cut back their use of fertilizer and adopt land management practices that help control runoff, such as planting cover crops. But as Gov. Kasich’s administration acknowledged in declaring the lake’s open waters impaired, voluntary programs haven’t been good enough.

“Farmers don’t wake up in the morning and say, ‘It’s a good day to pollute the environment,’” said Kristy Meyer, vice president for natural resources policy at the Ohio Environmental Council. “But they’re trying to maximize crop yield, and the old way of thinking about how to do that was to apply more fertilizer or manure. We need auditable common-sense standards to make sure farmers comply with what we call the four Rs: Only apply soil nutrients from the right source, at the right rate, at the right time, in the right place.

“In my church, I know some people won’t give it (the water) to their babies. They’re just not sure if they can trust it.”

- Keith Jordan

“Farmers should also work with certified professionals to put into place nutrient management plans for their farm fields, which will require a phase-in period, along with funding to assist farmers in implementing these practices,” Meyer added. “That’s not only the right way to control runoff, it’s the right business plan.”

In addition to tougher state laws and the pollution control measures that will be triggered by the impaired-waters designation, federal farm subsidies can play a major role in addressing the problem. Ohio farmers received almost $600 million in federal subsidies in 2016. Congress is expected to vote on a new farm bill this year, providing an opportunity to tie farmers’ eligibility for subsidies to compliance with sustainable practices.

“Farm subsidies need to be more strategic in terms of costs versus environmental benefits,” said Bihn. “We as taxpayers deserve to get the biggest bang for our buck.”

Nicholas Mandros, northwest director for the Ohio Environmental Council, is a native of Toledo who formerly worked in local government. He’s proud of the way the community responded to the 2014 water crisis and of the improvements the city has made to its water treatment facilities. But he said the crisis has “created a constant uncertainty every summer whether we will face another threat to our drinking water.”

“I’m not a bottled water guy. I’m used to walking to the kitchen and grabbing a glass of water and gulping it down and never think another thing about it. Now I don’t look at it that way.”

- Dave Spangler

Keith Jordan, the inner-city youth worker, said that three years after the 2014 crisis, some people still won’t drink Toledo’s tap water.

“In my church, I know some people won’t give it to their babies,” Jordan said. “They’re just not sure if they can trust it.”

Looking out at the lake from the deck of his charter boat, Dave Spangler said he also has second thoughts.

“I’m not a big bottled water guy,” he said. “I’m used to walking into the kitchen and grabbing a glass of water and gulping it down and never thinking another thing about it. Now I don’t look at it that way. But I shouldn’t have to think about it. No one should. Not here in the United States.”

Related Stories

October 16, 2017

September 20, 2017

July 26, 2017

References

- Michele C. Hlavsa et al., Recreational Water-Associated Disease Outbreaks – United States, 2009-2010. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Jan. 10, 2014. Available at www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6301a2.htm.

- Mary Figgatt et al., Harmful Algal Bloom-Associated Illnesses in Humans and Dogs Identified Through a Pilot Surveillance System — New York, 2015. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Nov. 3, 2017. Available at www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6643a5.htm.